Princeton University researchers have developed a new computer chip that promises to boost the performance of data centers that lie at the core of numerous online services such as email and social media.

The chip — called "Piton" after the metal spikes driven by rock climbers into mountainsides to aid in their ascent — was presented Aug. 23 at Hot Chips, a symposium on high-performance chips held in Cupertino, California.

Data centers — essentially giant warehouses packed with computer servers — support cloud-based services such as Gmail and Facebook, as well as store the staggeringly voluminous content available via the internet. Yet the computer chips at the heart of the biggest servers that route and process information often differ little from the chips in smaller servers or everyday personal computers.

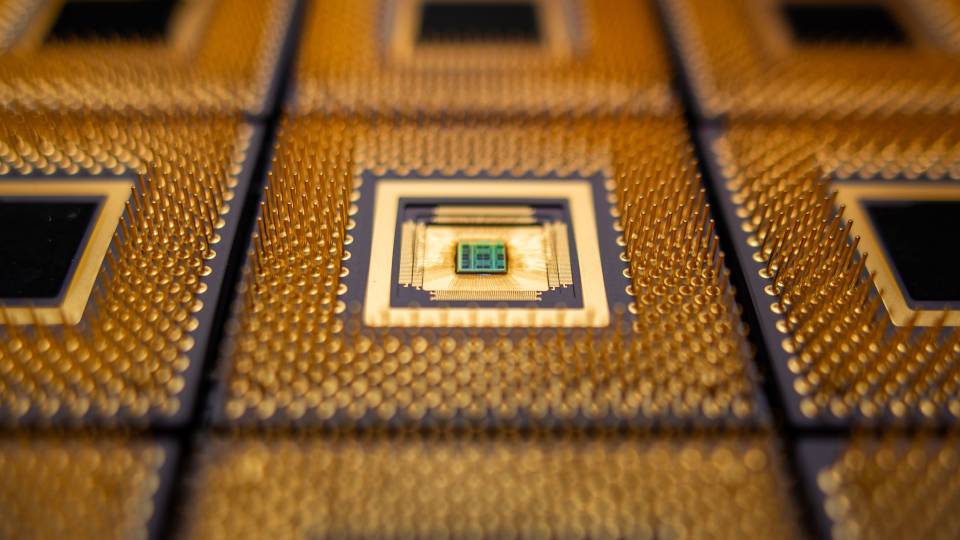

Princeton University researchers have developed a new computer chip called "Piton" (above) — after the metal spikes driven by rock climbers into mountainsides to aid in their ascent — that was designed specifically for massive computing systems. The chip could substantially increase processing speed while slashing energy usage, and is scalable, meaning that thousands of chips containing millions of independent processors can be connected into a single system. It was presented Aug. 23 at Hot Chips, a symposium on high-performance chips held in Cupertino, California. (Photo by David Wentzlaff, Department of Electrical Engineering)

The Princeton researchers designed their chip specifically for massive computing systems. Piton could substantially increase processing speed while slashing energy usage. The chip architecture is scalable — designs can be built that go from a dozen to several thousand cores, which are the independent processors that carry out the instructions in a computer program. Also, the architecture enables thousands of chips to be connected into a single system containing millions of cores.

"With Piton, we really sat down and rethought computer architecture in order to build a chip specifically for data centers and the cloud," said David Wentzlaff, a Princeton assistant professor of electrical engineering and associated faculty in the Department of Computer Science. "The chip we've made is among the largest chips ever built in academia and it shows how servers could run far more efficiently and cheaply."

The unveiling of Piton is a culmination of years of effort by Wentzlaff and his students. Michael McKeown, Wentzlaff's graduate student, will present at Hot Chips. Mohammad Shahrad, a graduate student in Wentzlaff's Princeton Parallel Group, said that creating "a physical piece of hardware in an academic setting is a rare and very special opportunity for computer architects."

The current version of the Piton chip measures 6 millimeters by 6 millimeters. The chip has more than 460 million transistors, each of which are as small as 32 nanometers — too small to be seen by anything but an electron microscope. The bulk of these transistors are contained in 25 cores. Most personal computer chips have four or eight cores. In general, more cores mean faster processing times, so long as software ably exploits the hardware's available cores to run operations in parallel. Therefore, computer manufacturers have turned to multi-core chips to squeeze further gains out of conventional approaches to computer hardware.

In recent years companies and academic institutions have produced chips with many dozens of cores — but the readily scalable architecture of Piton can enable thousands of cores on a single chip with half a billion cores in the data center, Wentzlaff said.

"What we have with Piton is really a prototype for future commercial server systems that could take advantage of a tremendous number of cores to speed up processing," Wentzlaff said.

The Piton chip's design focuses on exploiting commonality among programs running simultaneously on the same chip. One method to do this is called execution drafting. It works very much like the drafting in bicycle racing, when cyclists conserve energy by riding behind a lead rider who cuts through the air, creating a slipstream.

At a data center, multiple users often run programs that rely on similar operations at the processor level. The Piton chip's cores can recognize these instances and execute identical instructions consecutively, so that they flow one after another, like a line of drafting cyclists. Doing so can increase energy efficiency by about 20 percent compared to a standard core, the researchers said.

A second innovation incorporated into the Piton chip parcels out when competing programs access computer memory that exists off of the chip. Called a memory-traffic shaper, this function acts like a traffic cop at a busy intersection, considering each program's needs and adjusting memory requests and waving them through appropriately so they do not clog the system. This approach can yield an 18 percent increase in performance compared to conventional means of allocation.

The Piton chip also gains efficiency by its management of memory stored on the chip itself. This memory, known as the cache memory, is the fastest in the computer and used for frequently accessed information. In most designs, cache memory is shared across all of the chip's cores. But that strategy can backfire when multiple cores access and modify the cache memory. Piton sidesteps this problem by assigning areas of the cache and specific cores to dedicated applications. The researchers say the system can increase efficiency by 29 percent per chip. The researchers estimate that this savings would multiply as the system is deployed across millions of cores in a data center.

Members of the research team said these improvements could be implemented while keeping costs in line with current manufacturing standards. To hasten further developments leveraging and extending the Piton architecture, the Princeton researchers have made its design open source and thus available to the public and fellow researchers.

"We're very pleased with all that we've achieved with Piton in an academic setting, where there are far fewer resources than at large, commercial chipmakers," Wentzlaff said. "We're also happy to give out our design to the world as open source, which has long been commonplace for software, but is almost never done for hardware."

Piton was designed by the Princeton team and manufactured by IBM. Primary funding for the project has come from the National Science Foundation, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research. Other Princeton researchers involved in the project since its 2013 inception are: Yaosheng Fu, Tri Nguyen, Yanqi Zhou, Jonathan Balkind and Alexey Lavrov, all graduate students in the Princeton Parallel Group; Princeton alumni Matthew Matl '16, Xiaohua Liang '16 and Samuel Payne '14.