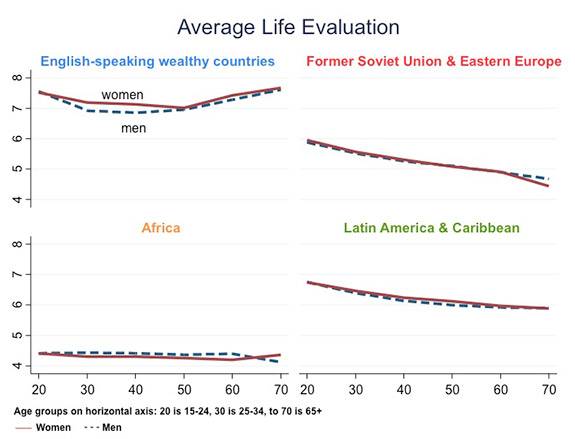

Life satisfaction dips around middle age and rises in older age in high-income, English-speaking countries, but that is not a universal pattern, according to a new report published in The Lancet as part of a special series on aging. In contrast, residents of other regions — such as the former Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa — grow increasingly less satisfied as they age.

The study — conducted by researchers from Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs(Link is external), Stony Brook University and University College London — highlights how residents of different regions across the world experience varying life-satisfaction levels and emotions as they age.

In the former Soviet Union and Eastern European countries, older residents reported very low rankings of life satisfaction compared with younger residents in those regions. This same pattern is seen in Latin America and Caribbean countries, though life satisfaction does not decrease as sharply as in the Eastern European countries. And in sub-Saharan Africa, life satisfaction is very low at all ages.

“Economic theory can predict a dip in well-being among the middle age in high-income, English-speaking countries,” said co-author Angus Deaton(Link is external), the Dwight D. Eisenhower Professor of Economics(Link is external) and International Affairs at the Wilson School. “What is interesting is that this pattern is not universal. Other regions, like the former Soviet Union, have been affected by the collapse of communism and other systems. Such events have affected the elderly who have lost a system that, however imperfect, gave meaning to their lives, and, in some cases, their pensions and health care.”

Life satisfaction dips around middle age and rises in older age in high-income, English-speaking countries, but that is not a universal pattern. As seen on the charts above, residents of other regions — such as the former Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, Latin America, the Caribbean and sub-Saharan Africa — grow increasingly less satisfied as they age. (Image by Ticiana Jardim Marini, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs)

The research team — which includes Professor Andrew Steptoe of University College London and Arthur A. Stone, who conducted the research at Stony Brook but is now a professor at the University of Southern California — also finds a two-way connection between physical health and well-being: poorer health leads to lower ratings of life satisfaction among the elderly, but higher life satisfaction seems to stave off physical health declines.

“Our findings suggest that health care systems should be concerned not only with illness and disability among the elderly but their psychological states as well,” Deaton said.

Using data collected by the Gallup World Poll and the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, the researchers looked at three measures of well-being: evaluative well-being, which focuses on evaluations of how satisfied people are with their lives; hedonic well-being, which is related to feelings or moods such as happiness, sadness and anger; and eudemonic well-being, which relates to judgments about the meaning and purpose of life. The researchers also looked at respondents’ ratings of physical health and pain.

Evaluative well-being was captured from participants using a Cantril ladder scale. This measure of well-being, developed half a century ago by Princeton social researcher Hadley Cantril, asks participants to visualize a ladder with steps numbered from zero at the bottom (worst possible life) to 10 at the top (best possible life).

When looking at life satisfaction scores across the regions, the researchers confirmed a well-known “U-shaped curve” that bottoms out between the ages of 45 and 54 in high-income, English speaking countries. These countries include the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. This curve indicates that, in these countries, middle-age residents report the lowest levels of life satisfaction, which eventually bounces back up after age 54.

“This finding is almost expected,” said Deaton. “This is the period at which wage rates typically peak and is the best time to work and earn the most, even at the expense of present well-being, so as to have increased wealth and well-being later in life.”

Outside of these high-income, English-speaking countries, however, the same U-shaped curve is not seen. All other regions report decreasing life-satisfaction levels as people age, with the former Soviet Union and Eastern European countries having the sharpest declines. The researchers attribute this phenomenon to the transitions these countries have experienced. They note that not being happy, which is uncommon in high-income, English-speaking countries, is quite common among transition countries, particularly among the elderly.

“The findings undoubtedly show the recent experiences of the region and the distress that these events have brought to older people,” Deaton said.

Gender, however, seems to make little difference. Men and women from the same regions have very similar levels of satisfaction, the researchers report.

Patterns in other measures of well-being

When looking at hedonic well-being — emotions and moods — across populations, the researchers find that older populations in high-income, English-speaking countries experience less stress, worry and anger than those who are middle-aged. A similar pattern is seen in the middle-income region of Latin America and Caribbean countries, where worry and stress peak in middle age, though not as sharply as in the Eastern European countries. And in sub-Saharan Africa, the researchers find that the prevalence of worry, stress and unhappiness increases just slightly with age.

In terms of gender, the differences between men and women in each region are slight. However, elderly women in former Soviet Union and Eastern European countries have substantially more worry, stress and pain than elderly men in those regions, regardless of the fact that the health of men in these countries has suffered more.

To determine survival rates among the elderly, the research team used data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, and they compared it with data on eudemonic well-being, or purpose in life. What emerges is a bidirectional relationship; when elderly people feel they have a purpose, their rates of survival increase. The researchers found that the proportion of deaths was 29.3 percent in the lowest life-satisfaction grouping and only 9.3 percent in the highest life-satisfaction grouping.

“Even though the results do not unequivocally show that eudemonic well-being is causally linked with mortality, the findings do raise intriguing possibilities about positive well-being being implicated in reduced risk to health,” the authors conclude.

In terms of physical pain, the fractions of young people reporting physical pain is similar across all regions, though the age-related trajectories for pain are much steeper in the former Soviet countries, sub-Saharan African and Latin America and Caribbean countries than in the high-income, English-speaking countries. Additionally, the pain divide between the old and young in former communist countries is much starker than the other regions.

While the research team agrees that progress is being made in terms of understanding how behavioral and biological elements play a role in subjective well-being, they agree that more work needs to be done.

“Investment in these research resources is essential,” said Deaton. “Most studies are of high-income countries and not those with low or middle incomes. However, cross-national surveys such as the Gallup World Poll and others are beginning to re-address the balance.”

The paper, “Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing,“(Link is external) was published Nov. 6, 2014, in The Lancet.

Funding is provided by the U.S. National Institute on Ageing (grants 2RO1AG7644-01A1 and 2RO1AG017644) and a consortium of U.K. Government departments coordinated by the Office for National Statistics. Both Deaton and Stone are supported by the U.S. National Institute on Aging through the National Bureau of Economic Research (grants 5R01AG040629-02 and P01 AG05842-14) and by the Gallup Organization. Stone also is supported by the British Heart Foundation.

The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing was developed by a team of researchers based at University College London, the Institute of Fiscal Studies and the National Centre for Social Research.