It was hot for mid-October. The humidity sank into the expansive depression of a former landfill near the Delaware and Raritan Canal owned by Princeton University. A high, overgrown rim along the site’s western edge deadened the afternoon sounds of the outside world hurrying along Washington Road. For the 13 freshmen in the seminar “Earth’s Environments and Ancient Civilizations,” the setting was the starting point of the most difficult scavenger hunt they’d encountered.

Two months earlier, instructors Adam Maloof(Link is external) and Frederik Simons(Link is external), both Princeton associate professors of geosciences(Link is external), led a crew that buried cow bones, block walls from Belgium, chunks of iron and other objects in the old landfill, all in random spots and at varying depths. Maloof and Simons recorded the precise locations of all of the objects.

In the time since, students in the class (designated the Richard L. Smith ’70 Freshman Seminar) have studied how to use global positioning systems (GPS), archaeological and geological data, geophysical technology, and computer programs that analyze hundreds of thousands of data points to seek and examine the buried remnants of lost civilizations. In this video, the freshmen familiarize themselves with the equipment used to unearth secrets underground.

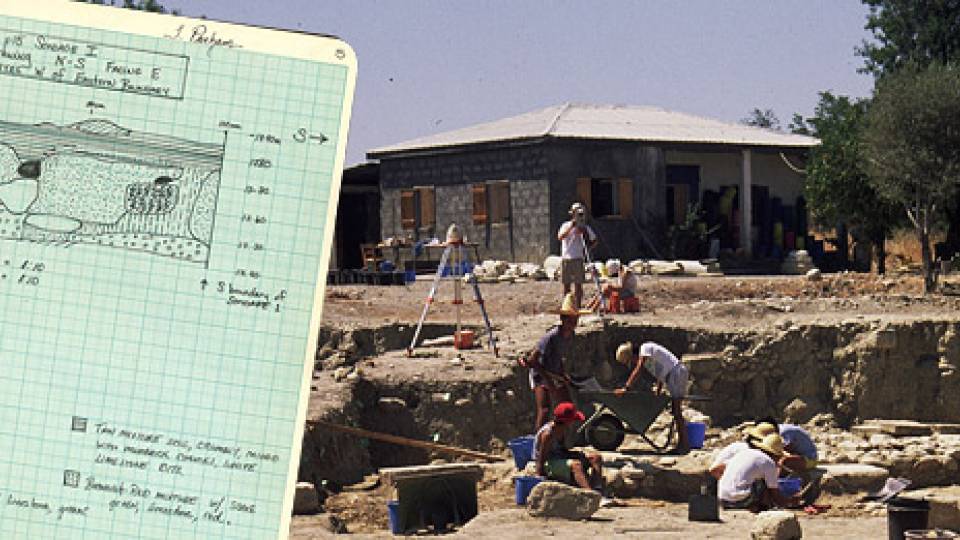

The course included a fall-recess trip to the University’s archaeological site in Cyprus, where students collected data for their final presentations Dec. 5 about how ancient civilizations altered the landscape and changed the environment — and vice versa. The course includes a third instructor, Joanna Smith(Link is external), a Cypriot Iron-Age scholar and a lecturer in the Department of Art and Archaeology(Link is external).

Two weeks before the Cyprus trip, the students were at the Princeton site to test the equipment they would use overseas, to identify any issues that could affect their readings in Cyprus. Though a test, it was far from the easy part — in fact, the hard part of this course had long since begun, said Abby Grosskopf, who has an interest in chemical and biological engineering(Link is external). In the past few weeks, she’d learned so much computer programming that, while she had no prior knowledge of computer science(Link is external), she now could write her own program.

“The class only meets once a week for three hours, but those three hours are the most intense of my week,” Grosskopf said. “Because it’s so intense you learn more.”

Grosskopf worked with Marcus Spiegel — a chemical and biological engineering major whose sister took the first offering of the seminar in 2011 and recommended it — to help create a 15 meter-by-15 meter (50 foot-by-50 foot) grid across the site.

The grid serves to organize the terrain before the students begin peering below using equipment such as ground-penetrating radar (GPR), explained Alain Plattner, a postdoctoral research associate who works with Simons and senior Kathleen Ryan, a teaching assistant to the class.

The GPR resembles a three-wheeled, all-terrain baby carriage with a car-battery strapped to its underside. The GPR sends an electromagnetic wave into the ground that bounces back within nanoseconds. The signal’s timing and intensity depend on the depth and material of the supposed ancient treasures it has located. But the GPR can be fickle — its sensitivity depends on the soil and terrain. The students would discover from their tests that the GPR works best on ground that was smoothed first, Maloof said.

Freshman Adrian Tasistro-Hart carefully treaded the rugged terrain as Grosskopf and Spiegel marked his path along the grid. He wore a backpack from which a GPS antenna extended to about 1 meter (3 feet) above his head, while in his hands he held a 1.5-meter (5-foot) pole fitted with a white cylinder connected to the pack. This was the magnetometer, which is used to prospect unknown terrain and detect the magnetic field of whatever is buried.

While not heavy, the magnetometer must be held perfectly still while in use in the field — which could be up to four hours. “If you move it, you change the recording,” Simons told the students. “You want to make sure the recording only changes when you’ve found something.”

For all its difficulty, the seminar has given Tasistro-Hart, who has an interest in atmospheric and oceanic sciences(Link is external), an appreciation for fieldwork and a new interest in geosciences, a discipline he had previously assumed was limited to “looking at rocks.”

“I expected the class to be difficult, but the challenge exceeded my expectations, which I’ve actually come to appreciate,” Tasistro-Hart said. “This class has taught me about ways of thinking and writing scientifically, as well as how to observe effectively.”

Students in the seminar attribute the learning experience to the enthusiasm and high standards of Maloof and Simons. Much like the site near campus, the intense data gathering and analysis are intended to simulate the real experience of working with colleagues to uncover artifacts hidden in the earth, Simons said. The students were not told what objects were buried at the site, nor where.

“They are learning to acquire data while working in a team,” Simons said. “The real exercise is after today when they will take the data and analyze them. Anything that comes through in the data will come through subtly. They’ll make as much as they can of it and then we’ll tell them what they’ve been looking at.”

Maloof said his most memorable work as an undergraduate was working alongside his professors rather than just being fed information. “Students learn how science actually works when they are observing and figuring things out together with the professor rather than just receiving a lecture — it’s more real and less of a show,” he said.

“Our goal is to teach them something they haven’t learned before — how real science works. Real data are messy and you have to really work for them. Collecting data is more than looking up facts online, analysis tools are more than using Google,” Maloof said. “We’re trying out projects no one has done before. I think it’s more exciting. It can seem harder to the students simply because it’s something they are not used to.”

The seminar’s final presentations are open to the public and begin at 1:30 p.m. Thursday, Dec. 5, in Guyot Hall, Room 178.