Almost anywhere he looks, Princeton professor Craig Arnold sees energy.

"Plants convert light to sugar -- this is chemical energy," Arnold told students in his freshman seminar on "Science and Technology for a Sustainable Future." "Cars take chemical energy and convert it to linear motion. We convert electrical energy into visible light by using a light bulb."

Arnold, who also is an associated faculty member of the Princeton Environmental Institute, shares with students his fascination with energy and his enthusiasm for innovation.

For Arnold, an associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering and an associated faculty member of the Princeton Environmental Institute, the intricacies of energy are central to his research. In his freshman seminar, Arnold conveys his fascination with the subject to "get students to think, 'I can make a difference.'"

Students said the seminar helps inform their strong interest in sustainability topics. Designated as the Donald P. Wilson '33 and Edna M. Wilson Freshman Seminar, the course is an outgrowth of Princeton's Grand Challenges Program, an interdisciplinary effort to address global environmental problems.

"I was the president of an environmental organization in high school, so I have always been interested in energy issues," said freshman Emily Eitches. "This class is so relevant and topical. Already I understand things so much more than I did before, such as how energy works, the societal and bureaucratic parts of energy production and how many people are involved in the process of creating energy."

In a recent session, Arnold told students about the life of the 19th-century English physicist and chemist Michael Faraday, whose experiments and discoveries led to the use of electricity in technology and whose experience provides a model for the challenges facing today's technology innovators.

From left, freshmen Charmaine Lee and Bradley Pelisek participate in a laboratory exercise using Legos, wire, magnets and voltage meters to construct small electric generators.

In the 1820s, the battery had recently been invented and people were just starting to understand electricity. Scientists thought of it like water flowing through a pipe, but did not appreciate that invisible forces occurring around the wires could be important, Arnold explained.

Faraday, he said, recognized an effect whereby changes in a magnetic field produced an electrical current. This concept is the basis for the modern-day electrical generator.

"By doing so he invented a new kind of physics" and demonstrated a new method that is at the heart of many of today's discussions about electricity, Arnold said. "These discoveries changed the world."

To demonstrate Faraday's law of induction -- if the magnetic field is altered, an electric current will travel through wire -- Arnold led the class through a lab in which the students used Legos, wire, magnets and voltage meters to construct small electric generators using Faraday's ideas.

The lesson on Faraday was not just about the discovery itself, but also what happened to Faraday's work. About 50 years elapsed before people were able to turn Faraday's discoveries into efficient and practical devices, Arnold said.

"Does this still happen today? It does, and this is a real problem. It is known as the 'valley of death,'" said Arnold, who also is an inventor. "If we invent the next great energy-producing widget in our lab, unless there's money, the political will and a technological need, it won't leave the lab and reach the public."

Faraday's life story is key for another reason, Arnold said. "Faraday had a fourth-grade education and did not know calculus from trigonometry, but he had an instinct and he wasn't afraid to ask the questions, 'What if I do this or that, or flip this around?" Arnold said. "Today scientists still must be fearless and ask, 'How does this work? How can I make it better? How can we avoid getting stuck in a rut and come at the problem from another place?'"

On a tour of the University's energy plant, manager Edward Borer (left) explains the environmental and financial benefits of Princeton's use of a technology known as cogeneration.

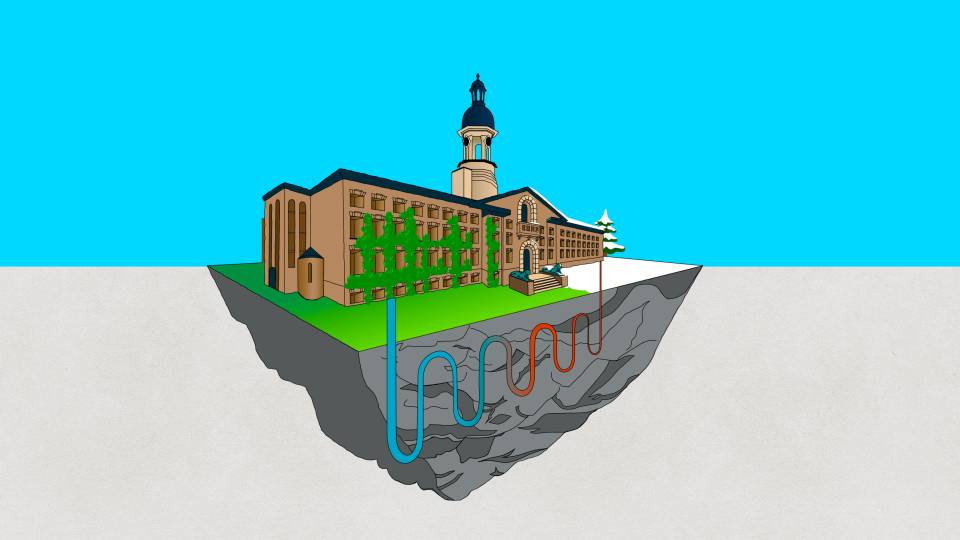

Field trips are part of the seminar as well. During a visit to the University's energy plant, which employs a technology known as cogeneration, the students learned how technologies evolve into more sustainable applications.

During a tour conducted by Edward Borer, the energy plant manager, students learned how the plant is powered by a large combustion engine. "We generate Princeton's electricity with big engines to turn the generator -- just like your Lego ones, only they are bigger, less flimsy and more precise," Borer said.

One problem with combustion engine technology, he noted, is that during this process heat is created and in most plants it is wasted. Princeton has overcome this problem by harvesting this heat for other purposes.

"This is the notion behind a cogeneration plant," Borer said. "Instead of the heat getting away through the chimney we use it on campus for a number of things, such as heating water and buildings. This ultimately saves the University a significant amount of electricity and money."

For their final projects, students will present tabletop demonstrations of sustainable energy technologies at the Liberty Science Center in Jersey City, N.J. The project presents an opportunity for the freshmen to be creative and gain insights into a subject about which they are passionate, Arnold said.

Freshman Max Rubin said, "The number one threat to the future of mankind is environmental deterioration. Now that I am a student at Princeton, I thought instead of waiting for someone else to find a solution, I should jump into the fray and try to solve it myself.

"I took this class because I want to understand more about sustainable energy solutions such as nuclear fusion, algae, solar and wind," Rubin said. "We probably won't be able to solve our environmental problems unless we use less energy. For this to happen, cultural and political change must occur before scientists can implement the technology needed to reduce our energy usage."