Princeton engineers have made a breakthrough in an 80-year-old quandary in quantum physics, paving the way for the development of new materials that could make electronic devices smaller and cars more energy efficient.

By reworking a theory first proposed by physicists in the 1920s, the researchers discovered a new way to predict important characteristics of a new material before it's been created. The new formula allows computers to model the properties of a material up to 100,000 times faster than previously possible and vastly expands the range of properties scientists can study.

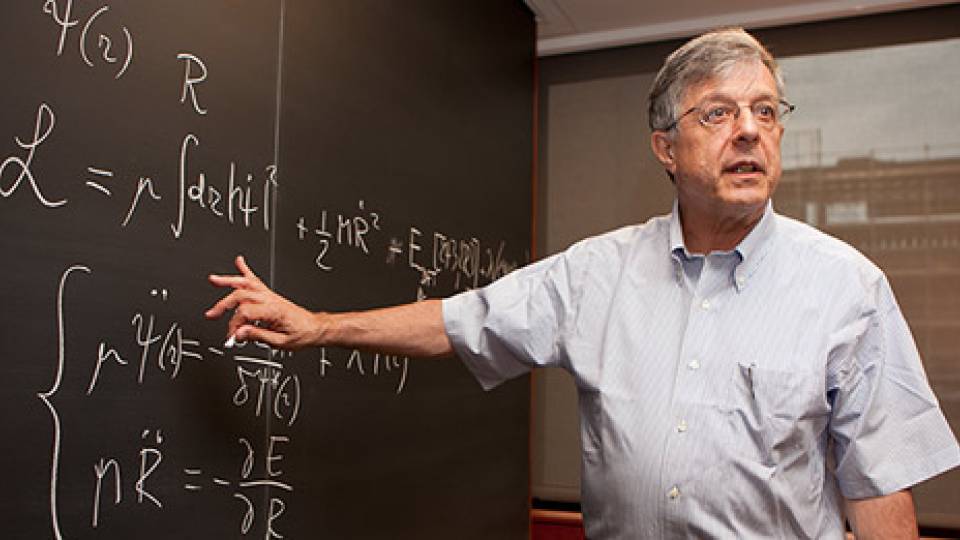

"The equation scientists were using before was inefficient and consumed huge amounts of computing power, so we were limited to modeling only a few hundred atoms of a perfect material," said Emily Carter, the engineering professor who led the project.

"But most materials aren't perfect," said Carter, the Arthur W. Marks '19 Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering and Applied and Computational Mathematics. "Important properties are actually determined by the flaws, but to understand those you need to look at thousands or tens of thousands of atoms so the defects are included. Using this new equation, we've been able to model up to a million atoms, so we get closer to the real properties of a substance."

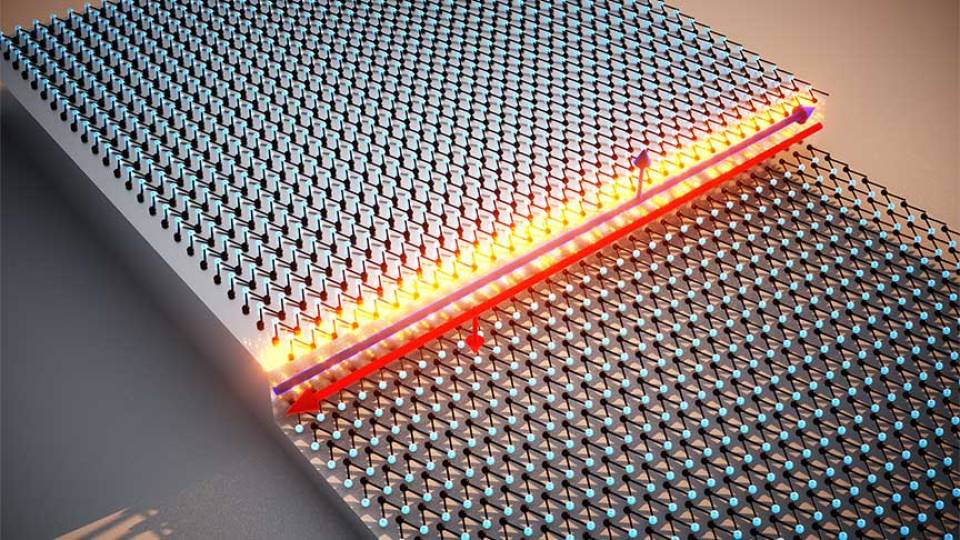

By offering a panoramic view of how substances behave in the real world, the theory gives scientists a tool for developing materials that can be used for designing new technologies. Car frames made from lighter, strong metal alloys, for instance, might make vehicles more energy efficient, and smaller, faster electronic devices might be produced using nanowires with diameters tens of thousands of times smaller than that of a human hair.

Paul Madden, a chemistry professor and provost of The Queen's College at Oxford University, who originally introduced Carter to this field of research, described the work as a "significant breakthrough" that could allow researchers to substantially expand the range of materials that can be studied in this manner. "This opens up a new class of material physics problems to realistic simulation," he said.

Professor Emily Carter and doctoral student Chen Huang developed a new way of predicting important properties of substances. The advance could speed the development of new materials and technologies. (Photo: Frank Wojciechowski)

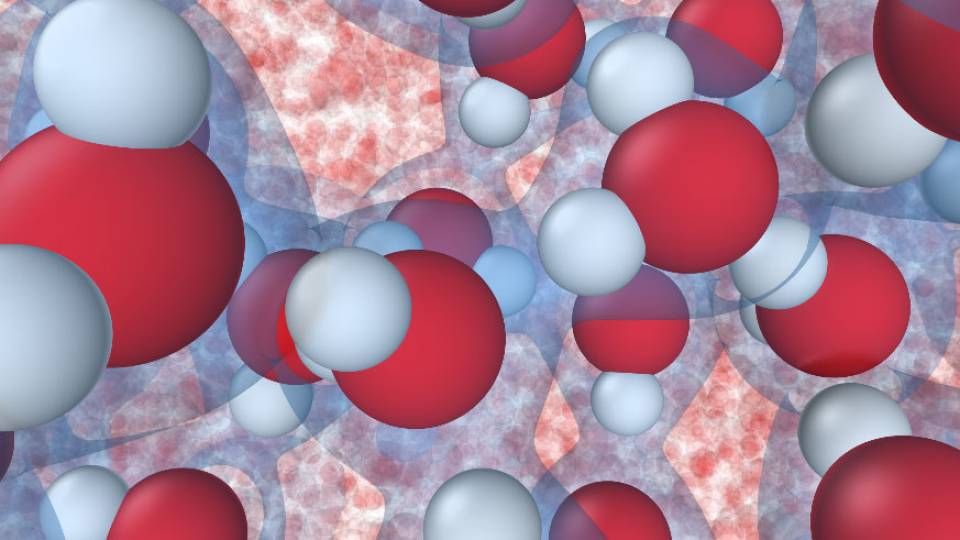

The new theory traces its lineage to the Thomas-Fermi equation, a concept proposed by Llewellyn Hilleth Thomas and Nobel laureate Enrico Fermi in 1927. The equation was a simple means of relating two fundamental characteristics of atoms and molecules. They theorized that the energy electrons possess as a result of their motion -- electron kinetic energy -- could be calculated based how the electrons are distributed in the material. Electrons that are confined to a small region have higher kinetic energy, for instance, while those spread over a large volume have lower energy.

Understanding this relationship is important because the distribution of electrons is easier to measure, while the energy of electrons is more useful in designing materials. Knowing the electron kinetic energy helps researchers determine the structure and other properties of a material, such as how it changes shape in response to physical stress. The catch was that Thomas and Fermi's concept was based on a theoretical gas, in which the electrons are spread evenly throughout. It could not be used to predict properties of real materials, in which electron density is less uniform.

The next major advance came in 1964, when another pair of scientists, Pierre Hohenberg and Walter Kohn, another Nobel laureate, proved that the concepts proposed by Thomas and Fermi could be applied to real materials. While they didn't derive a final, working equation for directly relating electron kinetic energy to the distribution of electrons, Hohenberg and Kohn laid the formal groundwork that proved such an equation exists. Scientists have been searching for a working theory ever since.

Carter began working on the problem in 1996 and produced a significant advance with two postdoctoral researchers in 1999, building on Hohenberg and Kohn's work. She has continued to whittle away at the problem since. "It would be wonderful if a perfect equation that explains all of this would just fall from the sky," she said. "But that isn't going to happen, so we've kept searching for a practical solution that helps us study materials."

In the absence of a solution, researchers have been calculating the energy of each atom from scratch to determine the properties of a substance. The laborious method bogs down the most powerful computers if more than a few hundred atoms are being considered, severely limiting the amount of a material and type of phenomena that can be studied.

Carter knew that using the concepts introduced by Thomas and Fermi would be far more efficient, because it would avoid having to process information on the state of each and every electron.

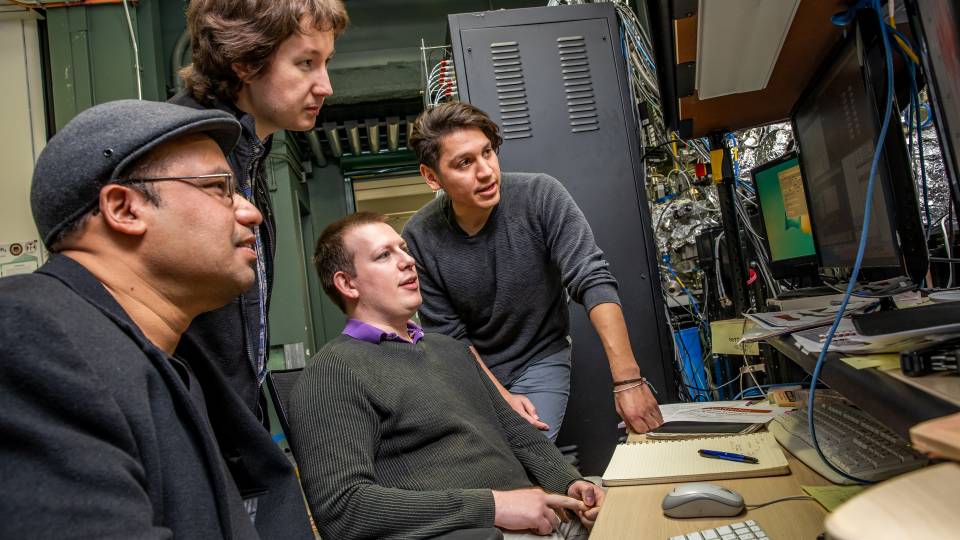

As they worked on the problem, Carter and Chen Huang, a doctoral student in physics, concluded that the key to the puzzle was addressing a disparity observed in Carter's earlier work. Carter and her group had developed an accurate working model for predicting the kinetic energy of electrons in simple metals. But when they tried to apply the same model to semiconductors -- the conductive materials used in modern electronic devices -- their predictions were no longer accurate.

"We needed to find out what we were missing that made the results so different between the semiconductors and metals," Huang said. "Then we realized that metals and semiconductors respond differently to electrical fields. Our model was missing this."

In the end, Huang said, the solution was a compromise. "By finding an equation that worked for these two types of materials, we found a model that works for a wide range of materials."

Their new model, published online Jan. 26 in Physical Review B, a journal of the American Physical Society, provides a practical method for predicting the kinetic energy of electrons in semiconductors from only the electron density. The research was funded by the National Science Foundation.

Coupled with advances published last year by Carter and Linda Hung, a graduate student in applied and computational mathematics, the new model extends the range of elements and quantities of material that can be accurately simulated.

The researchers hope that by moving beyond the concepts introduced by Thomas and Fermi more than 80 years ago, their work will speed future innovations. "Before people could only look at small bits of materials and perfect crystals," Carter said. "Now we can accurately apply quantum mechanics at scales of matter never possible before."